Interview,

Antonio Pappano on the London Symphony Orchestra

Congratulations on your appointment as Chief Conductor! I know you've already had your performance at the BBC Proms of Britten's War Requiem, but how does it feel as you're about to take the helm of this great orchestra?

Well, we've just been on tour, which is amazing. We went to Snape first of all, and then Warsaw, Ljubljana, and Gstaad, finishing in La Côte-Saint-André with the Berlioz Festival. So, we've already started! But in my season opening programme there is a premiere by James MacMillan, sandwiched in between two Scandinavian pieces: the Helios Overture of Nielsen and Sibelius 1. I can't wait to get stuck in with the audience in London.

It's a relationship that has been going on for many years. I've been conducting the orchestra since 1996, but now this is a time I can deepen that relationship. I'm very well aware of the fact that I have something very precious in my hands. Besides not wanting to screw it up, there's a fantastic opportunity to release this extraordinary amount of energy which comes from them. And I think I also have a decent amount of energy, which together can be a very positive thing. It's a mix of many different things: Mahler, Sibelius, Elgar, Saint-Saëns, and that's exactly the way I like it. I'm an eclectic musician and it's a moment to celebrate English music most of all: the strong passion that I have for it, which has developed over a relatively short amount of time, will be on show, and I do it with an open heart.

You mentioned MacMillan: your first recording for LSO Live was the Tenth Symphonies of both Peter Maxwell Davies and Andrzej Panufnik, and when you were at Covent Garden you oversaw several new operas from, amongst others, Birtwistle, Adès, Turnage, and George Benjamin. It seems that commissioning new music is very important to you, and presumably will play a big part in your programming?

Oh, absolutely. Last season, Alice Sara Ott and I performed a piece by Hannah Kendall; we've commissioned something new from her, and that will continue as we go forward. I think conductors do need to be in contact with the music that's being written today, but you can't just pay it lip service - you have to rehearse it, take it seriously, and try to get under its skin. You have to interpret, and that’s not the easiest thing to do with contemporary music. You have to be open to it, to have a feel for it, with an imagination that is different perhaps than if you're performing Bruckner or Brahms or even Britten. And I'm excited about doing that, because I love to study contemporary music. First, of course, it's a puzzle. You don't know where you are when you open the music. Then there's a period in which you start to see the strands, as with anything else. Importantly, you have to be the best salesman you can to the orchestra, because they look at their parts and they say, what is this? All of a sudden you put it together and you have to convince them first before you convince the public. I love that part of the job.

And do you welcome a composer's input through that rehearsal process?

Well, for example, with this MacMillan piece, we had a couple of run-throughs a few weeks ago with James there, and it was very interesting because I got to wrestle with the piece a bit, and so did the orchestra. But now he has described to me how he wants things shaped slightly differently from the way he's notated it, and that's a very valuable thing. When I was doing The Minotaur, to be sitting next to Harry Birtwistle every day during the rehearsals was just something that you can’t pay money for.

Talking about contemporary music leads me right back to the beginning: you've already mentioned 1996 as the first time you encountered the orchestra, in a recording of Puccini’s La rondine. You said in your book that they had just been doing a whole week of contemporary music, and that perhaps Puccini therefore came as a welcome change of pace! Do you remember your initial impressions of the orchestra when you conducted them that first time?

It's very rare that you start at the beginning in a recording - you usually start somewhere in the middle, because of the availability of different people at different times. But we started right at the beginning, and the beginning of La Rondine is quite rambunctious: I gave the downbeat, and the orchestra just exploded, it was like you're putting down the gas pedal on a Ferrari. The energy is genuine and it's still there today because the orchestra is full of genuine characters, genuine personalities, as human beings, and that comes through in their music making. There are several members of the orchestra that recorded with me, almost thirty years ago in 1996.

Naturally, a lot of the personnel have changed, but with the LSO it happens very gradually: it takes them a long time to decide who to let into the orchestra, frankly, because they're looking for those characters. And so since I've conducted the orchestra pretty regularly over these last years, I've seen the orchestra change, but a better way of saying it is that it has morphed gradually into what it is today. We have a lot of new people in the orchestra, together with the veterans. That combination is very valuable, and takes a long time to achieve to the right equilibrium, but it's fascinating because everybody's feeding off each other. The technical level is extraordinary, and that LSO energy, that combustibility, is there in spades.

You've mentioned their virtuosity, and I've heard you talk elsewhere about their intuition and emotional intelligence. When an orchestra is that good to start with, what's your approach in terms of how you decide what to work on? For example, I was fortunate enough to be able to sit in on the first orchestral rehearsal for your War Requiem Prom a few weeks ago, and I noticed that you were often explaining to them what the text was in various places to get your point across.

Yes, if there's text involved in a work, I think it's very important to share the general outline and sometimes the specific nature of what is being said, because with that little bit of information, they take it and run. They have that ability, and that's what I mean when I say emotional intelligence. But every work requires something from an orchestra and a conductor to make it work, whether it's mechanical things, technical things, or to achieve a narrative or a sense of strategy throughout the work to bring it to its culmination. These are things that need work, and I share a vision and my opinions about structure and how important phrasing is. You know, it's not always a four-bar structure. Sometimes it's five, sometimes it's six, sometimes it's seven, and so on. We as Western musicians are sometimes caught off-guard by five-bar phrases, even though Mozart uses them ad nauseam. So, just do the work that is necessary, and your personality, your backstory, your knowledge will come through. The word maestro means 'teacher', so whatever you need to teach or share or give impressions of, you just do it. But you talk to the orchestra with a certain respect and admiration. At the end of the day, you have to coax something, so sometimes you use your energy to say no, we're not close yet, this is what we need to achieve, or we did that better yesterday. Each piece demands something different.

Interestingly with the War Requiem, in the weeks leading up to our version of it, the London Symphony Chorus had performed it on tour with Teodor Currentzis, and so they already had an impression of how he did it. So my work was much more intense in the rehearsals to get what I felt was necessary and not what had maybe been done before. I’m not saying who's better or what's better, you know, just to give it a cohesion that belongs to the performance you are doing at that moment. Especially with the collaboration of the BBC Symphony Chorus for that concert, my role was to bring everybody onto the same page, and that's really exciting when you've got so many people for something that is such a “people piece”. To share that with 6,000 people was amazing. It's a piece that lives for an event like that - it doesn't do well in rehearsals or in preparation, it's fussy and you have to work on this and that. But the atmosphere in the hall was great.

With the chamber orchestra in the War Requiem, you said you wanted to conduct that yourself: is it more normal to have a second conductor, and what are the benefits of that?

The tradition was to have a second conductor. But nowadays, more often than not, the conductor does it all, because you can position the orchestra quite close to you, and certainly in terms of the energy, I think you can help shape it more organically if you're part of the whole thing.

With regard to your future plans with the orchestra, you've talked about your commitment to English music...is there anything else coming up that you’re able to share? Are there any composers you haven't conducted much that you'd like to explore? We've talked about operas, of course, and I notice that you’ll be returning to La rondine in December.

We're also doing Salome later in the season, in July. We'll be doing a programme to celebrate 200 years of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, and in the first half, Tippett’s A Child of Our Time. That's a crazy idea, and I hope I have the strength for it! I'm really looking forward to that. Also, the continuation of our Vaughan Williams symphony cycle is very important to me, because that's what spurred my interest to go much deeper into English music. A few years ago I had that experience of conducting the Fourth and Sixth symphonies, and so now we're just going to do them all. And that's a wonderful journey for me because they are all very different, one from the other. Some are more communicative, and what I'm looking forward to is trying to sell those ones that are a little bit more austere. Number Nine is coming up, and that will be paired with Five, which we’ve already recorded. We haven't started the editing yet, but that was an amazing experience. We toured Five in Germany, and it had such an effect on the audience, the spirituality of it. I mean, they never hear Vaughan Williams. I know Andrew Manze has, in his time in Germany, probably performed them up there, but other than that? So I was very gratified, and it moved me that the audience really got it.

Speaking of the Fourth and Sixth symphonies, I recorded a podcast with a couple of the orchestra members a few weeks ago about LSO Live, and we talked about your recording of those two symphonies and how Number Six was pretty much the last concert before lockdown. How was that for you, with that being the end and not being able to perform for so long afterwards?

Well, it was so meaningful, in fact, I said something to the audience at the end of it because I knew we weren't going to see them for a while. At the time, how naive were we? You know, we thought in a couple of months maybe… But I thanked them for coming to the concert and what it took for them to decide to come. The spirit that was in the room, making that music and capturing it on that record, was unique to our time, I think. And look what happened. I mean, it changed the world forever.

Markus Butter (baritone), London Symphony Orchestra, London Symphony Chorus, Sir Antonio Pappano

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC/ALAC/WAV, Hi-Res FLAC/ALAC/WAV

Angela Gheorghiu (Magda/Anna), Roberto Alagna (Ruggero/Roberto), William Matteuzzi (Prunier), Inva Mula (Lisette), Alberto Renaldi (Rambaldo), London Symphony Orchestra, Antonio Pappano

Available Formats: MP3, FLAC/ALAC/WAV

London Symphony Orchestra, Antonio Pappano

Available Formats: SACD, MP3, FLAC/ALAC/WAV, Hi-Res FLAC/ALAC/WAV

Masabane Cecilia Rangwanasha (soprano), Sarah Connolly (mezzo-soprano), Allan Clayton (tenor), Gerald Finley (bass), London Symphony Chorus, London Symphony Orchestra, Antonio Pappano

Available Formats: 2 SACDs, MP3, FLAC/ALAC/WAV, Hi-Res FLAC/ALAC/WAV, Hi-Res+ FLAC/ALAC/WAV

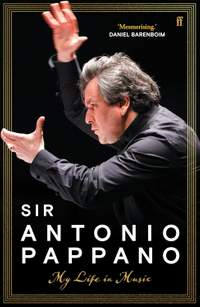

This memoir tells the moving tale of a conductor who, nurtured in childhood by his parents and their dedicated work ethic, went on to conduct at many of the most influential opera houses of the world. Pappano skilfully evokes an extensive selection from his wide-ranging repertoire and makes a compelling case for the potential classical music has to captivate new and wider audiences.

Available Format: Book